Category: Q&A — Published:

Whitechapel Gallery sits down with artist Jacob V Joyce to explore Nourishing Disruptions, a new mural for Pomell Way.

Whitechapel Gallery sits down with artist Jacob V Joyce to explore Nourishing Disruptions, a new mural for Pomell Way.

You’ve done many murals, including Radical Histories of Railton Road (2021), and the Joyce Guy Mural for the Mayor of London (2018). How did you become interested in mural painting? What are the benefits of working in this way?

I became interested in mural painting through squatting. I used to be part of a group called the London Queer Social Centre, which was a group of LGBTQ activists that would squat buildings and turn them into queer social centres. These spaces would have literary salons, queer martial arts classes, queer dance classes, queer tango, and stuff like that. They ran for about four years in different locations across South London, usually in tandem with London pride festivities, because we aligned ourselves as an anti-corporate pride movement. We saw ourselves as returning pride to its radical roots, not needing corporate sponsorship, but being more about a protest.

In all of the London Queer Social Centres, I painted murals. It felt like anyone could do anything. I remember that the first one I did in Kennington, people said we need to get some art in here, so I made a giant pterodactyl out of trash and hung it in the middle of the space. Squats represent a space that we’re not generally afforded to experiment at a large scale. Gradually, my murals became more and more political featuring people like Audrey Lorde, and Olive Morris. I think that’s where I cut my teeth practising painting murals.

For me, murals exist as public-facing archives, which often subvert a lot of the politics of the gallery. Certain people might not feel comfortable going into a gallery, or wouldn’t even think of going into a gallery. There’s something about an artwork that’s out in the street, which bypasses a lot of that. It feels like it engages with a much bigger audience.

What was the starting point for your latest mural, Nourishing Disruptions?

As with all the murals I have painted, serendipity played a big part in its creation. A few months before this commission was advertised, I was invited to do some ‘world-building’ workshops at Canon Barnett Primary School, which is right next to the mural.

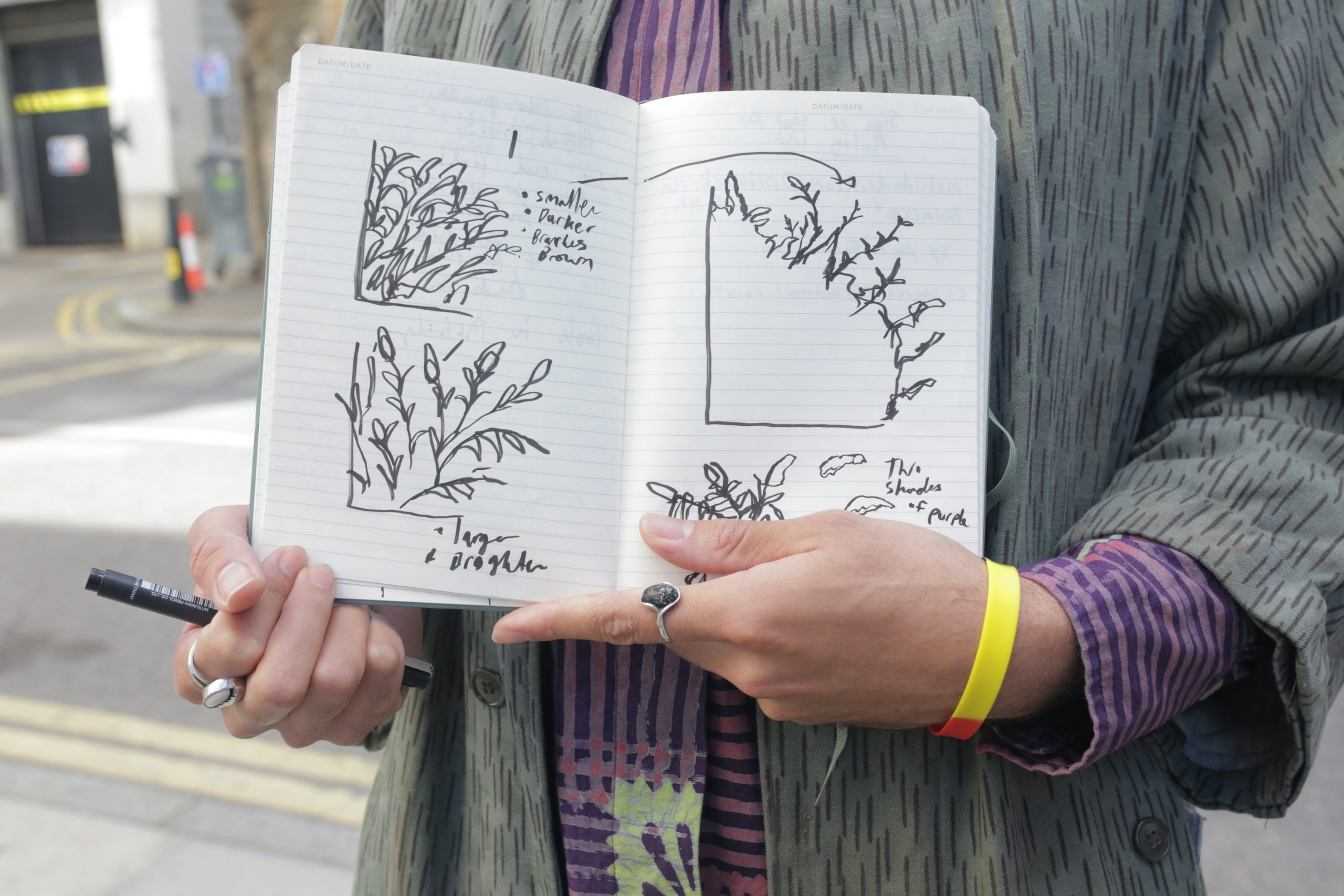

Under the umbrella title ‘Arty Parties’, myself and a bunch of other artists told these children that aliens were coming to their school. For my workshop, I asked the children to imagine how their school and local area could change to be more accommodating to aliens. I described the aliens as being a bit naughty, having trouble focusing in lessons, having a language barrier and not liking the food sometimes. The aliens were a metaphor for the children themselves, and how some of them might feel about school and about the local area. Looking at these kids drawing these worlds, creating windows into another world that would be less alienating for themselves and for other children that might have the same issues that they’re struggling with, I felt really inspired. I thought it’d be really cool to see something like this on a large scale; children making windows and changing the landscape.

Later, I was invited to do another workshop at Whitechapel Gallery with a group that I work with called the Museum of Homelessness, this is an organisation that works with people who have experienced homelessness. Again, it was based on alienation and strategies for resisting alienation. During the workshop, we gave everyone seed bombs, which contained Buddleia flowers. Nourishing Disruptions is a combination of energies that were left in the area during previous workshops that I was able to come back and collect up for this work.

I always want to link my work to local history: [Nourishing Disruptions includes] the Shaheed Minar monument at Altab Ali Park, and the Jagonari Women’s Centre. Normally my work focuses on black history, but I’m really interested in all anti-colonial histories and all histories of against hegemony: feminist histories, queer histories and histories of the global south.

Where does the title Nourishing Disruptions stem from?

I’m doing a PhD which is looking into the history of black arts education, specifically informal black arts education. I’m interested in the artists and the people who’ve used arts to challenge power to create space to counter hegemonic play and activities. A lot of my work is interested in this idea – what does it mean to nourish? Disruptions give energy to the space that disrupts what is normal and what is expected – I think that art can do that in a powerful and simple way.

The area of Whitechapel is really densely populated with skyscrapers, these big metal buildings. It feels quite imposing to have all these big structures all around you. I was thinking about the history of Whitechapel being an area that has historically been really badly polluted. How, in a kind of fantastical way, could this big landscape be disrupted?

For me, the only way that’s possible right now is through the imagination. A mural of a child using their imagination to disrupt the landscape and create space for green plants to grow felt almost like a wish, something I’d like to see manifested in the area.

What is the significance of the Buddleia flower?

The Buddleia is a plant which is tenacious, it’s beautiful, and it’s not afraid of ruins, it’s not afraid of growing in hostile environments. I think that is a good metaphor for migrant communities, and really, everyone. I think at some point we have to expand this to realise that we are all being destroyed by pollution, the destruction of the NHS, by the destruction of so many vital services for women, young people, the elderly, and sick people. The whole country is a hostile environment at this point. And I think that the Buddleia is something that, on the surface, you might think of it as kind of flimsy and just a beautiful thing, but it is tenacious; it will grow on your roof, it will grow in your gutter, it will grow, you know, anywhere that it can. It also supports life, they’re really food for butterflies. It felt like a nice way to say what I wanted to say without saying it.

The mural is full of symbols – on paint pots, on shop windows and on buildings. Where do you draw these from?

Some of them are symbols from Ghana which appear in African textiles and in woodwork from West Africa – they’ve also been adopted within a Pan-African context, they’re used quite widely across the Caribbean and in the Americas, especially ones like Sankofa which is an icon of a bird reaching back over its shoulder. Sankofa literally means to go back and get it, or retrieve something from the past. There are historical elements of the mural that are attempting to do this. Another symbol is the leaves of the dandelion, this is another plant which is tenacious and grows in the cracks. There are also some symbols which are borrowed from the Jagonari Women’s Centre.

Final question – what else are you working on at this moment?

I’m really happy to say that I am about to start a residency with the Museum of Homelessness over the next six months to deliver some community-facing large-scale artworks.

Joyce is a non-binary artist amplifying historical and nourishing new queer and decolonial narratives. Their work ranges from afro-futurist world-building workshops to mural painting, comic books and performance art. They have published several zines and illustrated international human rights campaigns for Out and Proud African LGBTI, Amnesty International, and Global Justice Now.

Jacob was awarded the TFL Arts Grant in 2019 and has seen their work displayed at Gasworks, Serpentine Galleries, Nottingham Contemporary and as part of the Tate Learning Programme.