Category: Documents of Contemporary Art — Published:

Patrick Staff, still from Weed Killer (2017). Courtesy the artist and Commonwealth and Council.

Patrick Staff, still from Weed Killer (2017). Courtesy the artist and Commonwealth and Council.

In an era defined by the Covid-19 pandemic, diet pills, record antidepressant usage, yoga and health-management apps, wellness is one of the defining issues of contemporary life, dictating every intimate aspect of our lives. Contemporary artists are increasingly confronting and reshaping these topics, incorporating personal approaches to health and identity in their work.

Part of the acclaimed series of anthologies which document major themes and ideas in contemporary art, Health explores the ethical, aesthetic and political significance of practices, positions and theories connected to health in contemporary art. In celebration of the book’s publication, we’re sharing a timely excerpt from acclaimed poet and essayist Anne Boyer on the Covid-19 pandemic.

If you’re interested in learning more, be sure to get a copy of Health from our bookstore and register for the online discussion on 12 November 2020. Editor Bárbara Rodríguez Muñoz will be in conversation with artist Khairani Barokka, Pedro Neves Marques and Patricia Domínguez to contribute to our thinking about how health intersects with sexuality, ethnicity, gender, class and coloniality.

This Virus by Anne Boyer

so violent a rudeness, untenanted by any tangible form – Edgar Allan Poe

It is a shame that to understand this virus, we must understand math, which to the many of us who were denied a decent math education in school, exists mostly as a phantasm: exponentiality no easier to grasp than the hand of a ghost. And now the health of many depends on a general capacity to believe in the future tangibility of the present intangibles. We must not only now understand exponential growth, but also the difference between sly things, like the deadly distance between 1% and .1%.

In the meantime, the world’s eugenicists-in-chiefs appear to lick their lips at the prospect of the deaths of the elderly, sick and poor. The vicious denialism of Trump, Johnson and Bolsanaro is the logic that also governed yesterday’s every day misery, made grand to fit today’s catastrophe. For a certain class, the death of what they consider ‘the unproductive’ comes as a messy but not unwelcome event. This is why you see that cadaverous look in these guys’ eyes at the press conferences in which they stand in their bloated suits, mumbling administrative deceptions about the flu, about testing. We know to believe what they do, not what they say: finance gets emergency aid and the hospitals don’t. In the meantime, CPAC (Conservative Political Action Conference) itself might have become a polo-shirt-and-pepe version of the Masque of the Red Death.

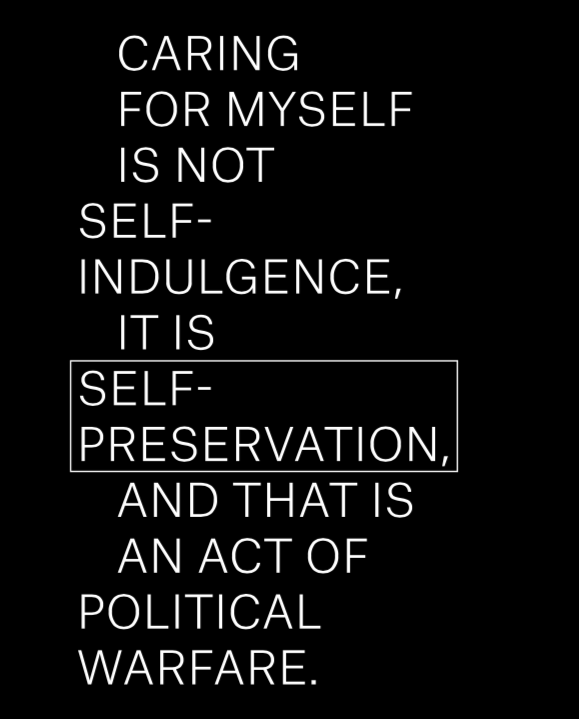

These are the same types who say the only thing to fear is fear, which of course is not true, because fear educates our care for each other – we fear a sick person might be made sicker, or that a poor person’s life might be made even more miserable, and we do whatever we can to protect them because we fear a version of human life in which everyone lives for themselves only. I am not the least bit afraid of this kind of fear, for fear is a vital and necessary part of love. And this fear, which I love, is right now particularly justified, because we have a pernicious virus that travels inside the healthy to sicken and kill the already fragile, and therefore requires that the healthy and strong deepen their moral commitments for the benefit of the sick and weak. We must learn to do good for the good of the stranger now. We now have to live as daily evidence that we believe there is value in the lives of the cancer patient, the elderly person, the disabled one, the ones in unthinkable living conditions, crowded and at risk.

Total misery in the coming days is not a total inevitability: we have a capacity to respond today. We can practice excellent hygiene, stop leaving messes for cleaners, disinfect our common spaces. We can try our best to get what we need to get by for a while. We can – today, right now – organise mutual aid networks among our existing social contacts, make plans to care for the vulnerable, prepare supplies for those who will get sick. We can provide shelter for the people who don’t have it, offer to be a support for anyone feeling crazy from the news, promise to take care of someone’s pets or kids if they get sick. We can provide important information to those who have been deceived or ignored. We can protect those who are unfairly stigmatised and discriminated against. We can sew masks and make disinfection kits to give to those who will be caring for the sick at home.

We can also go on a general strike, which now has a double purpose – stay at home, refuse to work, refuse to go to school, refuse to shop, refuse as much as possible to get sick or make others so. We can shout at the top of our lungs and demonstrate in our every action that the lives of the vulnerable matter, that the deaths of the sick and the elderly and the poor and imprisoned from this virus are unacceptable. The prisoners must be freed. The elderly must be cared for. Everyone must have safe housing. The sick must be supported without fear of losing jobs or being bankrupt by medical costs. The cleaners, health care workers, and other carers on the front line must have everything they need to stay safe. This virus makes what has always been the case even more emphatically so.

We also must engage in large scale social distancing. The way social distancing works requires faith: we must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love. We face such a strange task, here, to come together in spirit and keep a distance in body at the same time. We can do it. I am writing this because I want the good in us to break through the layers of hateful nonsense we’ve been drowning in. I think we can be good, but we also must prepare for an amplification of evil’s evil. The time when the invisible becomes visible is at hand.