Published:

On the occasion of museums and galleries reopening across the world, we’re reflecting on what makes art and art spaces special. They breathe life and colour into neighbourhoods; they share stories and ask questions. They have the power to teach, to shift, to celebrate and critique. That’s why, for over one hundred years, Whitechapel Gallery has worked to bring art to the heart of East London.

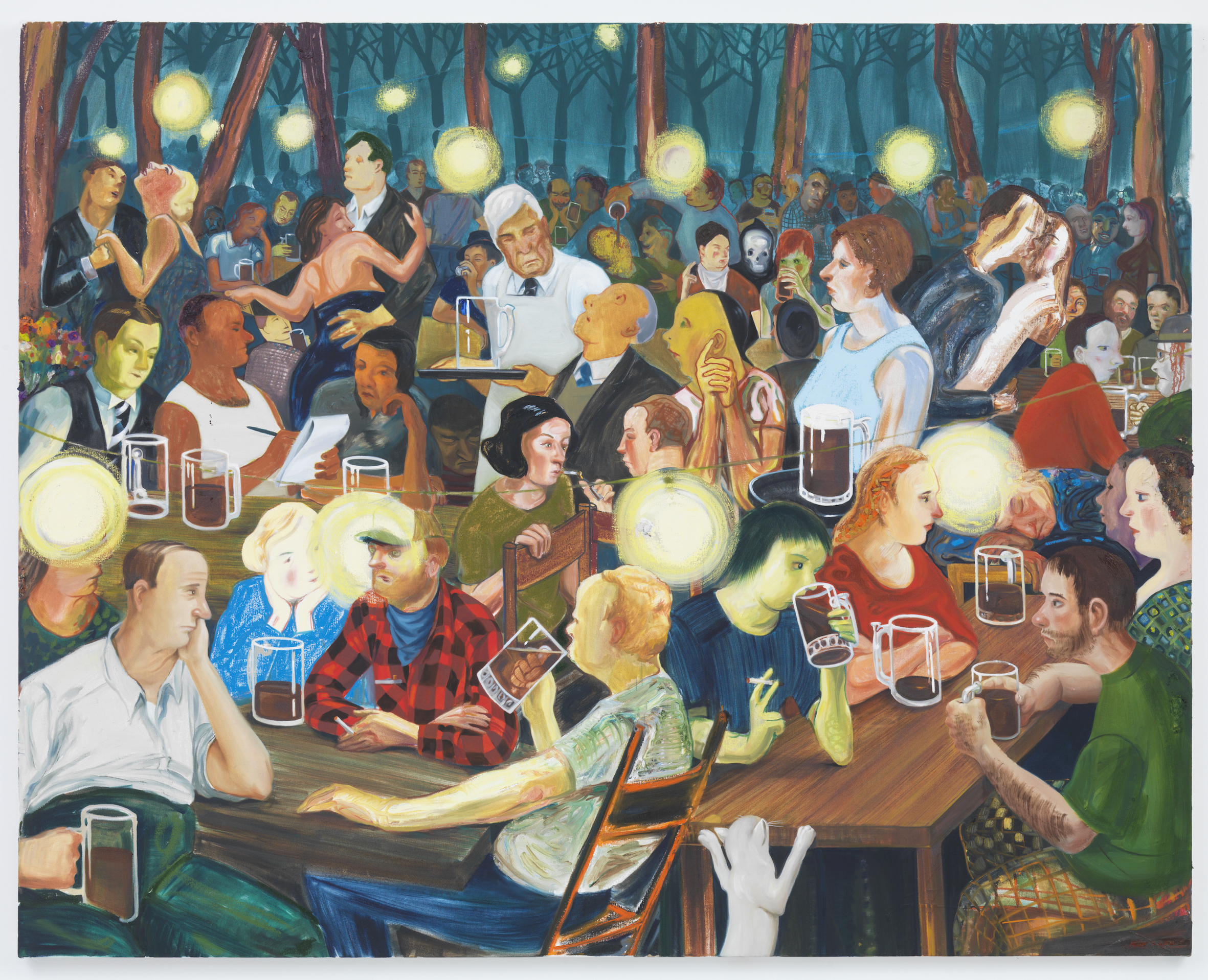

Nicole Eisenman, Brooklyn Biergarten II, 2008, Oil on canvas. Valeria and Gregorio Napoleone Collection, London

Nicole Eisenman, Brooklyn Biergarten II, 2008, Oil on canvas. Valeria and Gregorio Napoleone Collection, London

Nicole Eisenman (b.1965, Verdun, France) studied at Rhode Island School of Design (1987) and spent a year in Rome enthralled by Renaissance painting. She uses allegory and satire to engage with contemporary social subjects, including gender and sexuality, the inequalities of wealth and power and the tropes of Western figurative painting. Observing everyday human behaviour, Eisenman moves across genres and subjects, from large groups of figures in busy compositions, to couples in domestic scenes and expressionist portraits. ‘Applying paint’ for Eisenman, ‘is like any language; communication in life varies, we talk in colloquialisms, we talk formally, we talk and act appropriately or inappropriately.

Brooklyn Biergarten II (2008) is part of a group of works representing the artist’s social milieu. Dozens of figures sit around tables in a romantically-lit pavilion. Could this be a bar in Williamsburg, or something more sinister? Despite the flowing drinks, the characters appear frozen and distant. Perhaps this is because Death has joined the party, sitting at their own table with a skeletal face and dark hood.

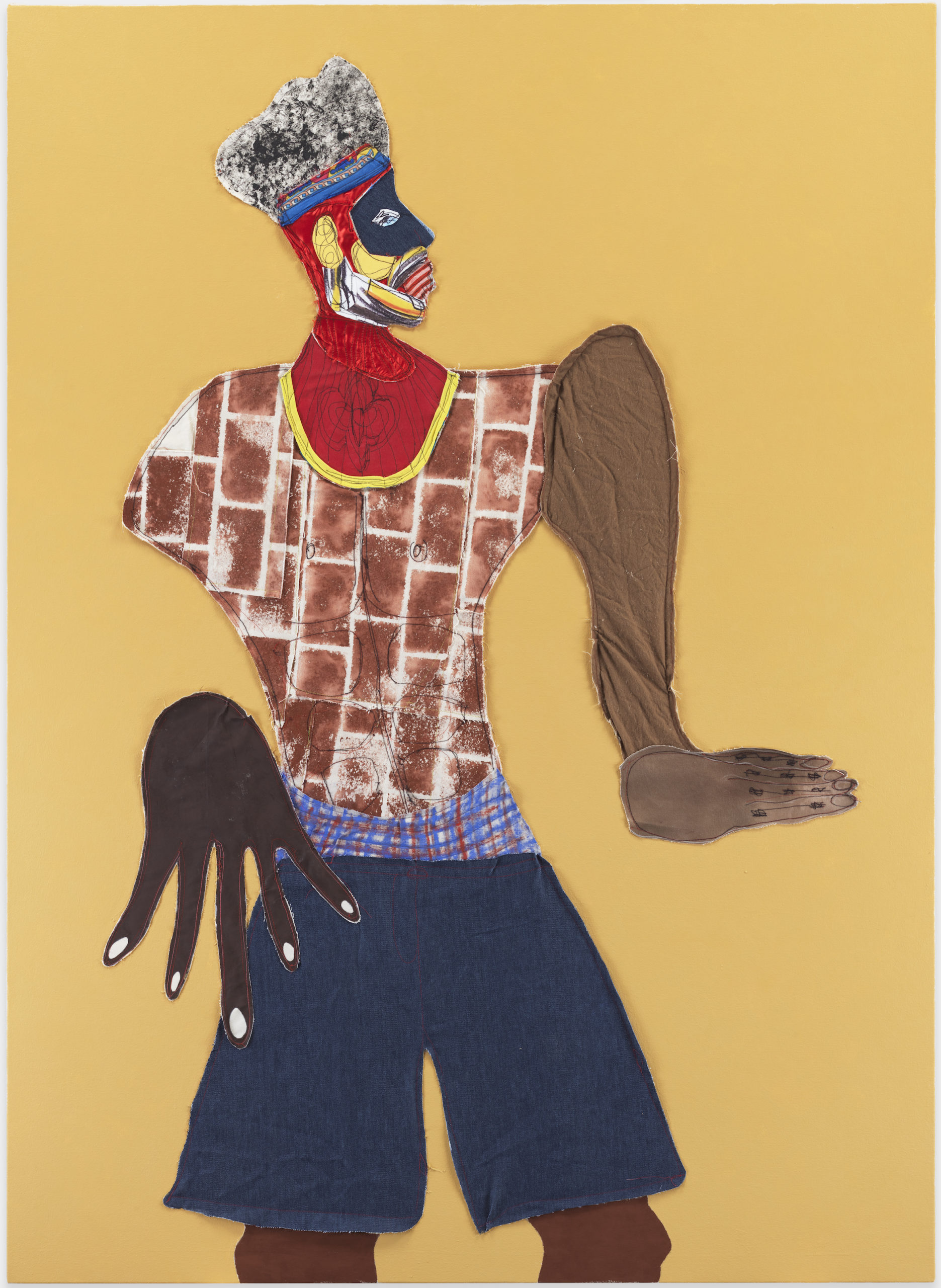

Tschabalala Self, Fade, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias Gallery, London. Photo: Damian Griffiths

Tschabalala Self, Fade, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias Gallery, London. Photo: Damian Griffiths

Tschabalala Self (b.1990, New York) studied printmaking and painting at Bard College and Yale School of Art. Self depicts black figures, often female, in a bold, exaggerated and flattened style with a combination of sewn, printed, and painted materials. She learned quilt making and sewing from maternal family members and uses these assemblage and appliqué techniques to confront the stereotypical and sexualized representation of black bodies, referencing Jacob Lawrence and Faith Ringgold as artistic touchstones. Working with fabric scraps, she prefers ‘materials that are of the world because they keep that energy from their original purpose’

Fade (2019) is titled after the hairstyle sported by the male figure. In a further exaggeration of both feminine and masculine characteristics, his abs are delicately outlined in thread.

Cecily Brown, Lucky Beach, 2017, Oil on linen, 210.8 x 170.2 cm, Collection of Laura and Barry Townsley, London. © Cecily Brown. Courtesy of the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery, and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

Cecily Brown, Lucky Beach, 2017, Oil on linen, 210.8 x 170.2 cm, Collection of Laura and Barry Townsley, London. © Cecily Brown. Courtesy of the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery, and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

After studying painting at the Slade School of Art in the early 1990s, Cecily Brown (b.1969, London) left London, where painting had fallen out of favour among her generation, and settled in New York. Hovering between representation and a type of abstraction associated with the 1950s New York action painters, Brown’s canvases blend bold brushwork, human figures, animals and elements from the landscape or setting. Maid’s Day Off (2005) is an elaborate mise-en-scène, a bourgeois interior brimming with evidence of disarray and debauchery straight out of William Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress (1732– 34). The imagery is difficult to discern and the title adds to the ambiguity. Has the maid been party to the goings-on or did they happen in her absence?

Recent paintings by Brown take the sea as a point of departure. Her palette in Lucky Beach (2017) is inspired by the unique northern light she experienced on the coast in Denmark.

Carlos Bunga, Something Necessary and Useful, 2020, installation view. Photo: Nick Seaton. Courtesy Whitechapel Gallery.

Carlos Bunga, Something Necessary and Useful, 2020, installation view. Photo: Nick Seaton. Courtesy Whitechapel Gallery.

‘When we walk in that space we are walking between the past and the future and we are the present’. Carlos Bunga (b. 1976, Portugal) creates monumental structures out of everyday materials to propose architecture as transitory and corporeal in Something Necessary and Useful.

Using cardboard, tape and paint, Bunga creates cavernous structures and imaginary buildings to explore the transitory and corporeal nature of architecture. Bunga’s family had escaped the violence of the Angolan War of Independence in the 1970s only to experience the volatility of life at the edge of Portuguese society. Immersing us in his towering structures, Bunga then sweeps them away. Through these cycles of construction and destruction, he explores the mutating city and dispossession.