Category: Commissions — Published:

Embodying the role of the artist as social activist in her major new exhibition, Can You Hear Me?,

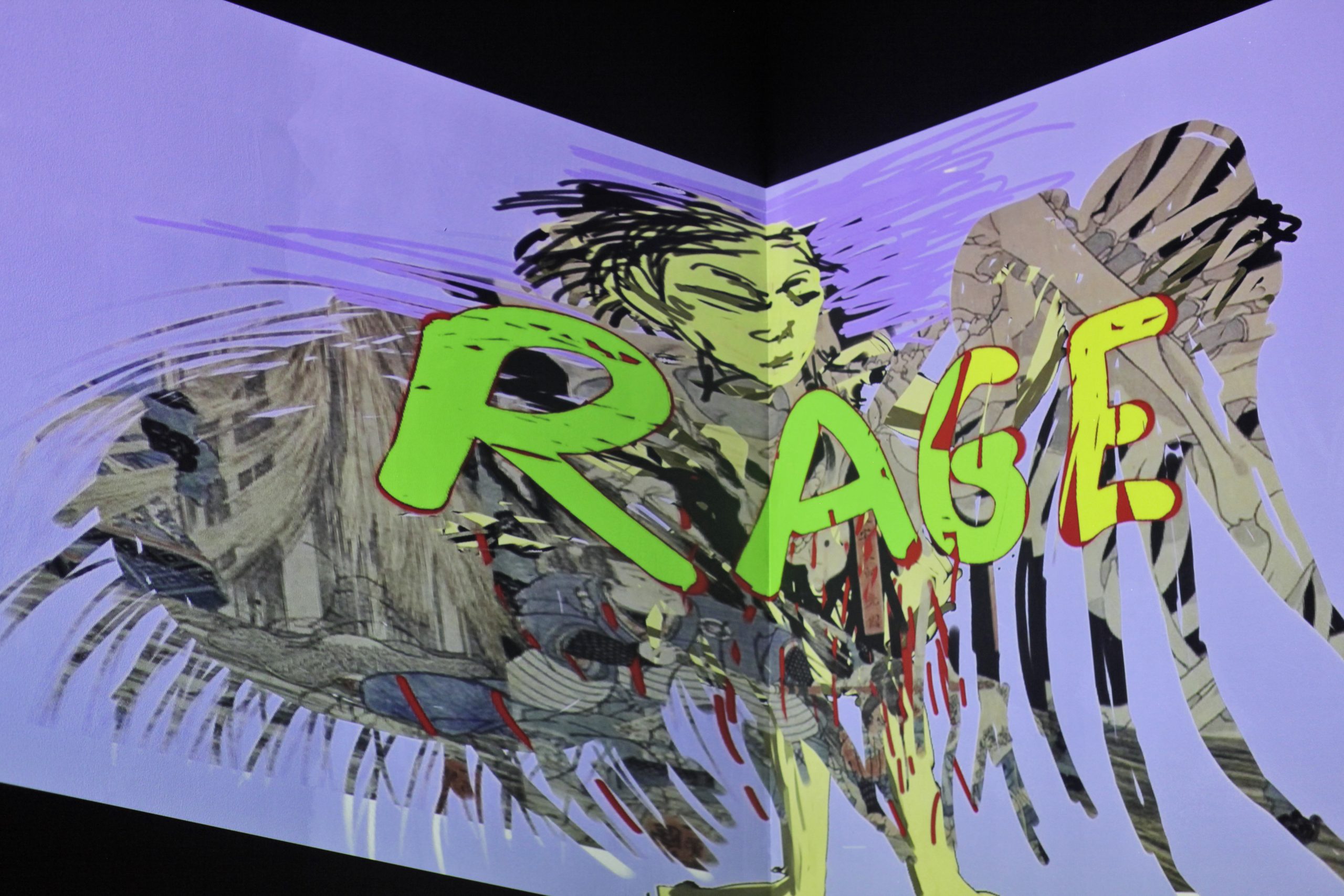

Nalini Malani (b. 1946, Karachi, Undivided India) gives voice to the marginalised through visual stories which takes the form of a multi-layered, immersive installation, exploring themes of violence, feminism, politics, racial tensions and post-colonial legacies.

You can find out more in our podcast, Hear, Now, which sees Malani in conversation with Curator

Emily Butler. Here we share an extract from a text by the artist about her Whitechapel Gallery commission and the inspirations behind her Animation Chamber. The full version is available in the exhibition catalogue, which hit the shelves earlier this month.

Can You Hear Me?

When I was invited for the 2020 Whitechapel Gallery commission, I heard many voices in my head. I studied the history of the Gallery and the Passmore Edwards Library, called ‘University of the Ghetto’, and their original socialist ideals appealed to me as a place where artists could realise their vision, as a catalyst for personal and political transformation – specifically, and specially, its rich history of exhibition pioneering women artists such as Joan Jonas (1979), Eva Hesse (1979), Frida Khalo (1982), Cindy Sherman (1991) and the Guerrilla Girls (2016). Equally I was interested in how the spaces were used by artists in a new manner, for example for the solo exhibitions of Jackson Pollock (1958), Mark Rothko (1961) and Robert Rauschenberg (1964), their scale and colour achieved an unrivalled fit with the gallery space. The idea of bringing out a ‘Cathedral in the Gallery’ intrigued me since I started making my Wall Drawings and Videoplays.

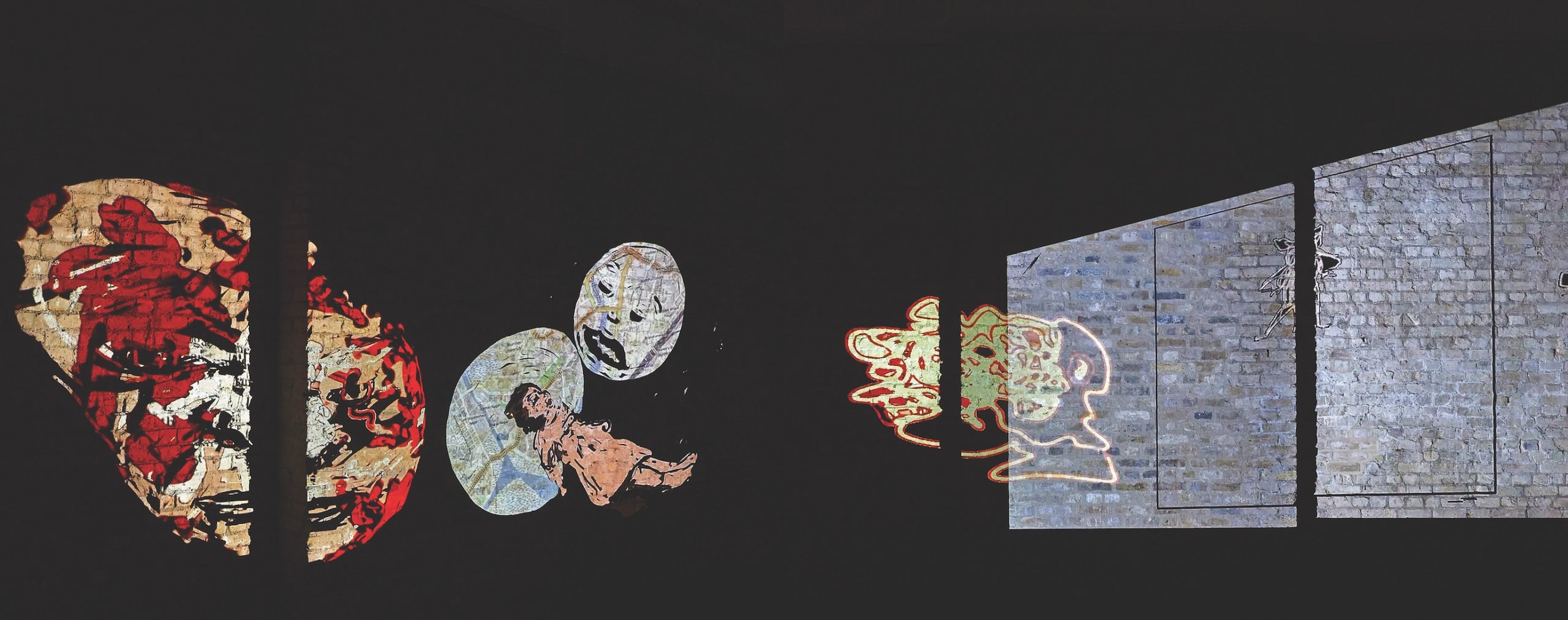

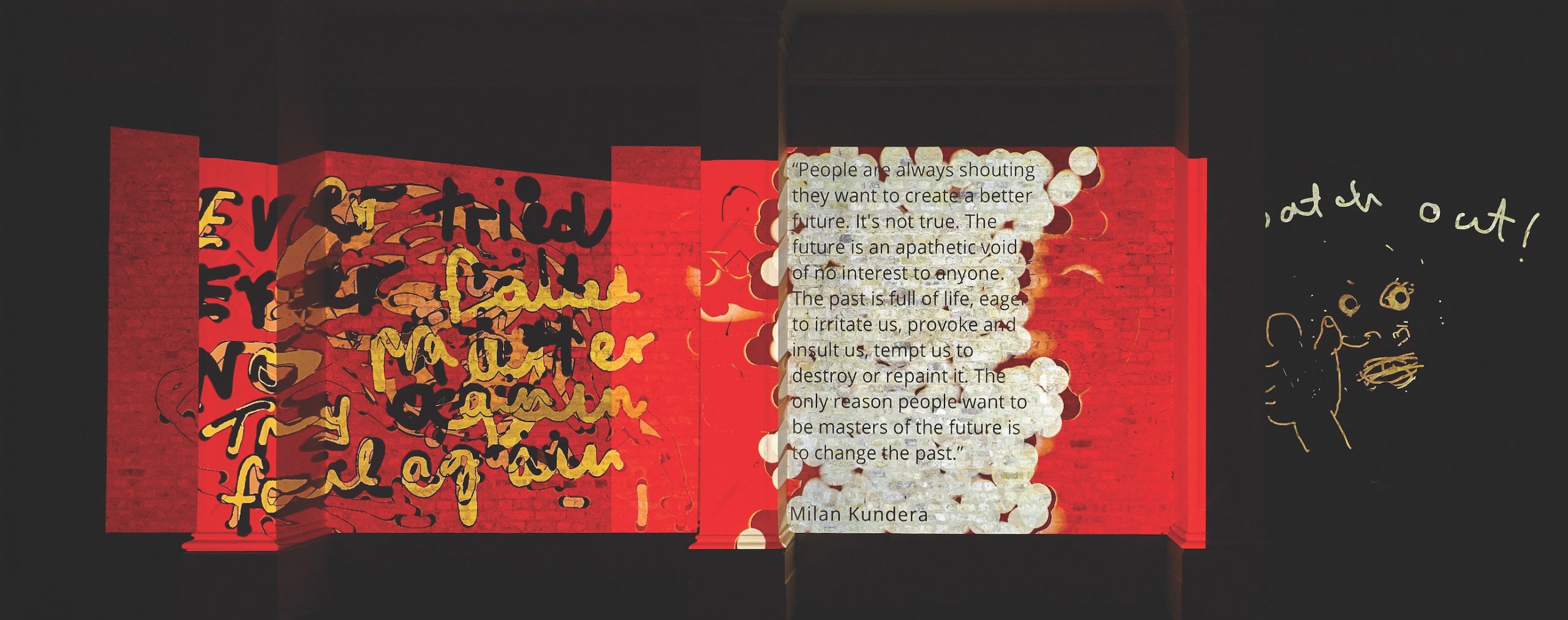

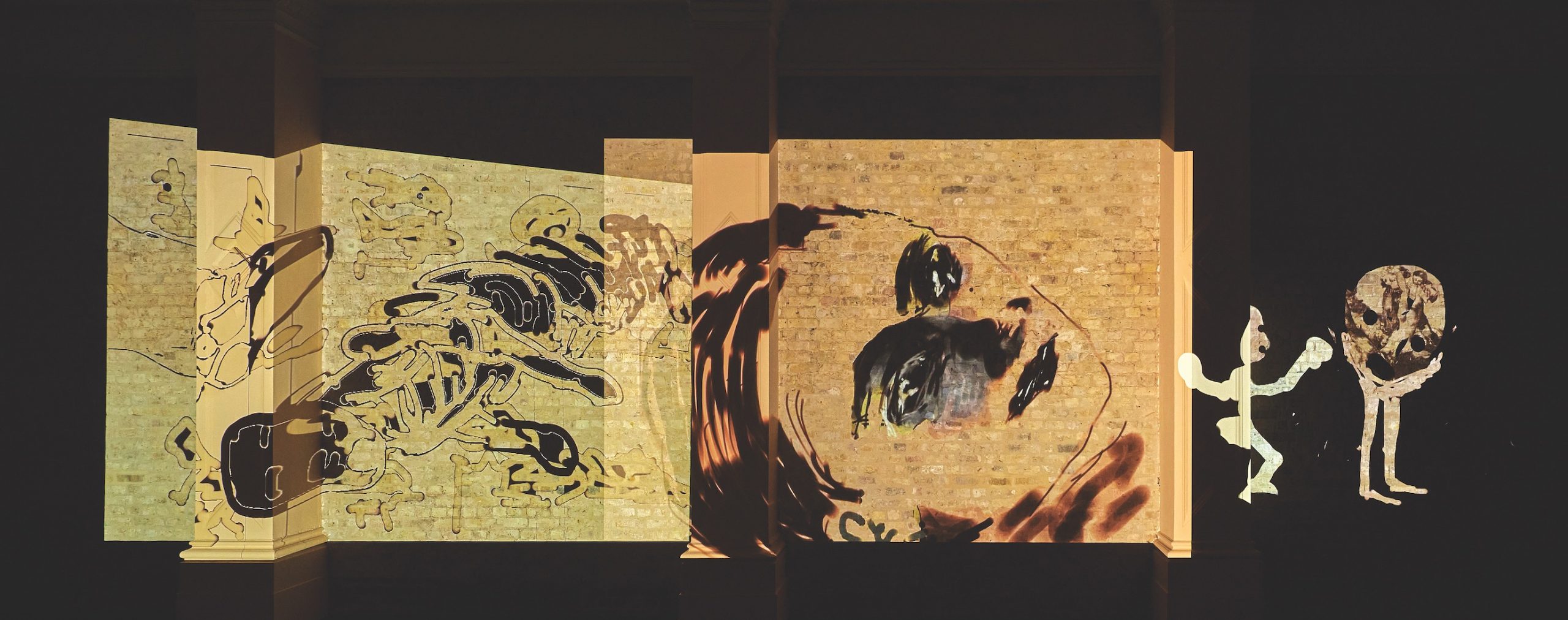

To honour the history of the building and the latest architectural intervention by Robbrecht en Daem and Witherford Watson Mann Architects, I decided to keep the room intact, where the exposed original Victorian brick walls would become shelves to “hold” the unfolding animation projections, as a series of open book pages, partly overlapping and collaging over each other. The roughness of these bricks, in contrast to the usual white cube space, or in my case the Animation Chamber in a room that is usually painted raven black, triggered my mind with unusual associations. This happened when reading about the Miró exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1989. In Paul Bonaventura’s essay for The Whitechapel Art Gallery Centenary Review he noted that “Miró experienced a crisis in his work in 1929, when he was 36, which has been identified as anti-painting because of his often-quoted remark that he wanted to ‘murder’ painting”, and that Catherine Lampert wrote in the exhibition catalogue that ‘[n]aturally there was much more to this withdrawal an the story involves the overlap of a Catalan instinct for rough materials and collage, […] and the growing threat to freedom sweeping through Spain in the 1930s’. It reminded me of the growing global make dictatorial threat of 2020. How could one extend or seek anew this language now? My aim with these politically incisive notebook animations was to expand the visual vocabulary, which in times of distress comes into the public domain, and becomes an instrument for people to apprehend the world in an alternative way. For instance, how to visualse the paradox that when the Indian constitution itself is at odds with the government and a bone of contention – where the citizen is arrested for treason when she raises her voice by quoting the constitution in a supposed democratic country?

The Animation Chamber contains the voices in my head and my heart, stimulating how the mind works, as ordered chaos. The making of these individual works often starts with a quote as a reaction to what has sparked or irritated my mind, from writers or images which give me a kind of graffiti, such as Brecht, Orwell, or artists such as Goya or Grosz, that would form a collage/montage. They form a bridge language, but are also not from my country, and therefore the subversion can bypass censorship. I draw them directly on an iPad with my index finger, not with the Apple Pencil. There is sensitivity with the fingertip, which is erotic, raw and there is something very direct about this process of drawing, rubbing, scratching and erasing, to do with the messing around in one’s mind. I feel like a woman with thoughts and fantasies shooting from my head.

I would list the different typologies: the socio-political, the more ‘abstract’ ones, the feminine/masculine, the satirical and personal ones. If one were to observe one’s own mind these factors play a part in the whirlpool of the unconscious. In that sense the Animation Chamber resembles the psychoanalyst’s chamber where the thought machine is provided a rehearsal chamber. So the chamber acts as a deterrent to ‘acting out’. Similarly, my Animation Chamber works as a ‘member membrane’ of quotes from people who have addressed the issues that concern me now. Melding my images with the voices, of for instance Wisława Szymborska or Veena Das, gives a sense of direct agency. As such the Animation Chamber works like a stream of consciousness, one thing telescoping into the other, recreating the complexity of thought the way time works at any given moment.

– Nalini Malani

Nalini Malani’s commission, Can You Hear Me?, is free to visit and runs until 6 June 2021. Keep your eyes on our website to book your ticket when the Gallery re-opens.